Is More Always Better?

In his most recent book, When More Is Not Better: Overcoming America’s Obsession With Economic Efficiency, Roger Martin offers a novel perspective on the question of whether economic growth can be a cure-all for society’s challenges.

As a mainstream business professor and globally respected former dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Business, Martin is certainly no proponent of the “limits to growth” paradigm, which gained notoriety in the 1970s when the Club of Rome questioned whether exponential growth could go on indefinitely on a planet with finite resources.

But he does believe that a focus by businesses on “endless maximization” of a singular objective – efficiency – has contributed to an unsustainably unequal distribution of the benefits of growth … one that threatens faith in the legitimacy of market capitalism. Martin notes:

Throughout the first nearly two and a half centuries of America’s existence as a sovereign state, most citizens experienced an advance in their economic status. Based on that trend, Americans have, unsurprisingly, used their votes … to perpetuate capitalism as America’s economic system. But that consistent economic advance has stalled.

The data backs up Martin’s assertion: The growth of personal income has fallen precipitously since World War II. According to the United States Regional Economic Analysis Project, the United States' real per capita personal income was growing at an annualized rate of 3.49% in the 1960s. Since then, it has averaged less than 3% from 1970 to 2000 and less than 2% since 2000. Pew Research reports that from 2000 to 2018, the growth in household income has slowed to an annual average rate of a meager 0.3%.

The problem, according to Martin, is that our pursuit of efficiency hasn’t just caused individual economic growth to stall – it’s now turning into a destructive force.

How?

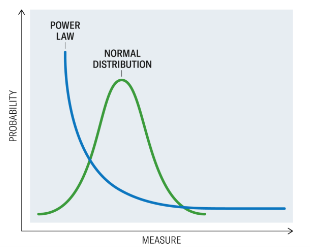

By incentivizing business executives to focus on applying too much pressure, too much connectedness and too much pursuit of perfection in the operation of their enterprises. The pursuit of efficiency has transformed what was for centuries a relatively normal, bell-shaped or Gaussian distribution of wealth into a Pareto distribution, where enormous wealth is concentrated at one extreme end of the curve.

A Gaussian, or bell curve, distribution (green) versus a Pareto, or power-law, distribution (blue).

Source: Harvard Business Review.

Martin continues:

Capitalism is no longer unambiguously about everyone working hard and getting ahead – it is about the benefit of overall growth flowing so disproportionately to rich people that there just isn’t enough left for average Americans to consistently advance. … The modern worlds of economics and business have adopted as their core rule the opposite of balance: maximization of a singular objective.

To spread the benefits of economic growth more equitably, he argues, “leaders must violate the core rule under which they are asked to operate: More is always better.”

I recently read an article in the Wall Street Journal that urged business executives “raised on the gospel of hard work and max effort” to attain peak professional and personal effectiveness by “taking it down a notch.” The article title: “Try Hard, But Not That Hard. 85% is the Magic Number.”

Could the same rule hold true for the economy as a whole? Or, as one Oxford economist once asked, would the [political and social] costs of deliberate non-growth be astronomical?”

What I like about Martin’s approach is that he doesn’t pit growth vs. non-growth. Instead, he argues for treating the economy as a natural system, like a rainforest – “complex and adaptive” and non-linear, instead of a perfectible machine. “Because the outcomes in a complex adaptive system aren’t linear, incremental and predictable,” he writes optimistically, “we have no idea just how good a future American democratic capitalism could have.”

Readers of this blog will know that I have been serving for the past year as an Executive in Residence at Wake Forest University’s Center for Capitalism. This is the second of a series of articles on the state of American Capitalism.

The information reflected on this page are Baird expert opinions today and are subject to change. The information provided here has not taken into consideration the investment goals or needs of any specific investor and investors should not make any investment decisions based solely on this information. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. All investments have some level of risk, and investors have different time horizons, goals and risk tolerances, so speak to your Baird Financial Advisor before taking action. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the speaker and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the firm.